[Series] FESCARO's Automotive Cybersecurity FAQs

FESCARO has been operating the ‘FAQs Series’ to address cybersecurity issues for stakeholders in the automotive industry. We have conducted live webinars on four key topics, and the expert panel from FESCARO provided answers to the most commonly asked questions from industry professionals. If you missed a webinar on a topic that interests you, you can access both the recorded video and a text summary (FAQs) at the following link.

# FAQs Series

1. Cybersecurity Strategies for Tiers (Emerging-OEMs oriented)

2. Comprehensive Guide on Cybersecurity Solutions & Engineering

3. Cybersecurity Testing method based on VTA Success Stories

4. ECU Cybersecurity guidance : From production to post-mass production

5. How Korea’s Motor Vehicle Management Act Amendment impacts OEMs and Tiers

The webinar, <Cybersecurity Testing method based on VTA Success Stories>, hosted by FESCARO in September, ended successfully. We welcomed over 100 pre-registered attendees from about 60 companies to our webinar, which we prepared in response to consistent requests for security testing methods.

Automakers request cybersecurity tests on ECUs and vehicles as part of the Vehicle Type Approval (VTA) process. They also expect controller developer companies to ensure a reliable level of cybersecurity. Have you wondered about the ins and outs of VTA cybersecurity testing Know-how? FESCARO's Red Team, with its proven success record, is here to provide clear insights. Let's dive in together.

■ FESCARO's Red Team has,

• Achieved VTA in collaboration with global automakers

• Conducted security tests on 150 controllers and actual vehicles, both in stationary and driving environments

• Designed and implemented over 100 test items and 200 test cases, and are in continuous development

■ QUESTION LIST

■ VIDEO Ver.

■ TEXT Ver.

1. Various

types of automotive security tests

Before diving into the diverse

types of automotive security tests, let's first look at the necessity of

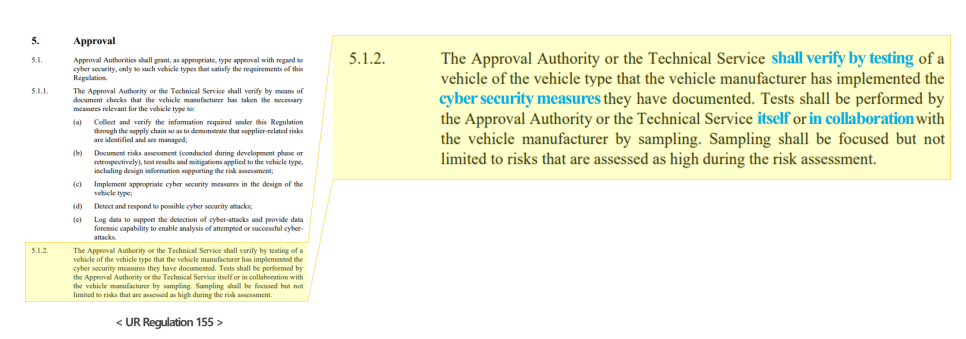

security testing. As mandated by UN R155, an international automotive

cybersecurity regulation, automakers are required to secure certifications for

both the Cyber Security Management System (CSMS) and Vehicle Type Approval

(VTA). Section 5 of UN R155 delineates the cybersecurity requirements vehicles

should adhere to and outlines the evaluation criteria.

Specifically, Section 5.1.2 mandates that any approval authority (AA) that performs approval or technical service provider (TS) that performs approval on its behalf shall verify by testing of a vehicle of the vehicle type that the vehicle manufacturer has implemented the cybersecurity measures they have documented.' While security testing can be directly conducted by the AA or TS, or in collaboration with automakers, it's more typical for AA or TS to review and assess the testing performed by the automakers.

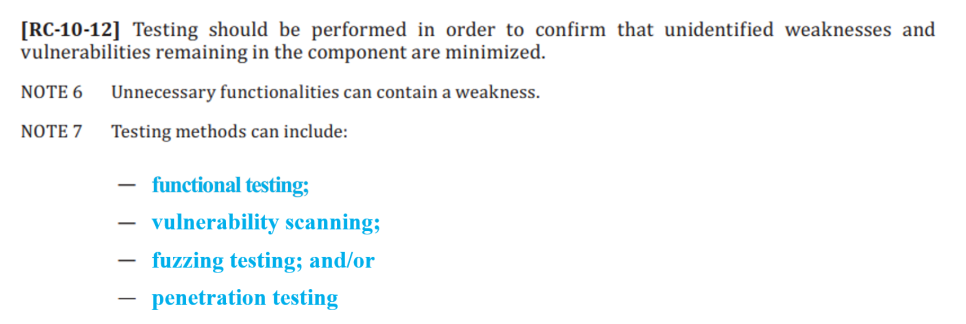

In the end, the AA, TS, and automakers are required to conduct security testing. The specific tests that need to be performed are outlined in ISO/SAE 21434, a standard for automotive cybersecurity engineering. The tests are generally categorized into functional testing, vulnerability scanning, fuzzing testing, and penetration testing.

Let's begin with functional testing. Functional testing might already be familiar to many Tier companies. Tiers typically receive and analyze security requirements from OEMs, subsequently integrate it into the design, and then embody it in the software or hardware of controllers. The essence of functional testing is to validate that these requirements have been properly implemented. Some automakers offer both design and evaluation specifications, and testing is performed according to the evaluation specifications.

Moving on to vulnerability scanning. This test aims to detect any remaining known vulnerabilities in the controller's software or hardware. Given the prevalent use of open-source in controller SW development nowadays, this test becomes pivotal to ascertain that open-source vulnerabilities have been adequately addressed.

The fuzzing test involves introducing random, undefined data, primarily targeting the vehicle's controller or its external interfaces. The purpose of this process is to discover potential flaws or vulnerabilities in either the software or hardware.

Lastly, penetration testing is a type of mock hacking. It seeks to evaluate the robustness of existing security measures by mimicking real-world hacking attempts against vehicles or controllers.

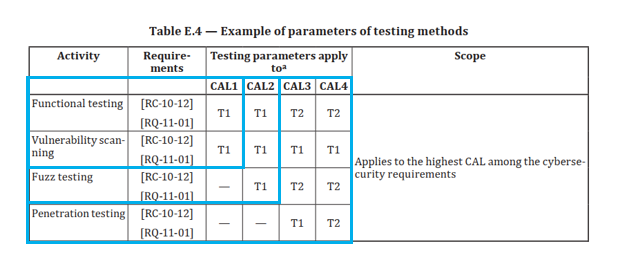

To secure a VTA in line with UN R155, one must demonstrate that vehicle cybersecurity has undergone rigorous validation via such tests. Now, you might wonder if all controllers need to undergo all four tests. Fortunately, the answer is no. ISO/SAE 21434 Annex E delineates specific testing approaches corresponding to each cybersecurity assurance level (CAL).

Controllers classified under CAL 1 are required to undergo both functional testing and vulnerability scanning. For those under CAL 2, fuzzing testing is added to the mix. Meanwhile, controllers classified under CAL 3 and 4 must additionally undergo mock hacking. For reference, T2 refers to a more advanced testing technique. The specific CAL assigned is determined through a process called TARA (Threat Analysis and Risk Assessment), conducted at the controller level.

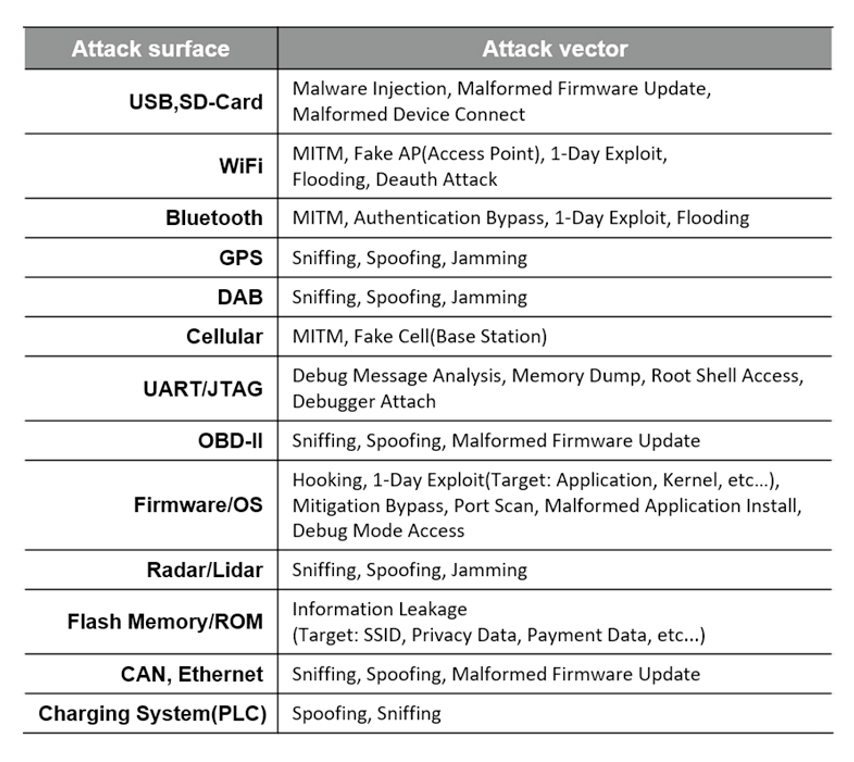

2. Are there any security tests that examiners check for VTA?

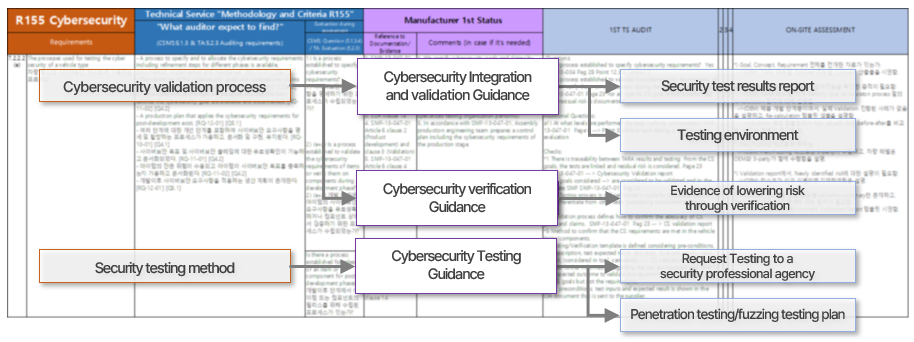

During the VTA process, what do examiners prioritize? They focus on determining if the actual vehicles have undergone testing according to the cybersecurity validation process established by the automaker and whether every activity within this validation process is traceable. They also scrutinize the validity of the previously submitted documentary evidence. Moreover, when conducting on-site inspections, they ensure that the previously submitted test results align with the actual test outcomes.

Let's take a closer look at the VTA requirements as stipulated by UN R155 and what examiners focus on. UN R155 states that automakers should perform appropriate and sufficient testing to verify the effectiveness of their cybersecurity measures. Throughout the VTA process, examiners check whether automakers have performed the tests properly by posing seven questions below.

The regulation doesn't offer explicit guidelines. The above questions serve as a reference, created by FESCARO based on our firsthand experiences during the VTA certification process. For those pursuing VTA, it's advisable to be well-prepared for these questions.

3. Are there any dependencies between TARA and security tests?

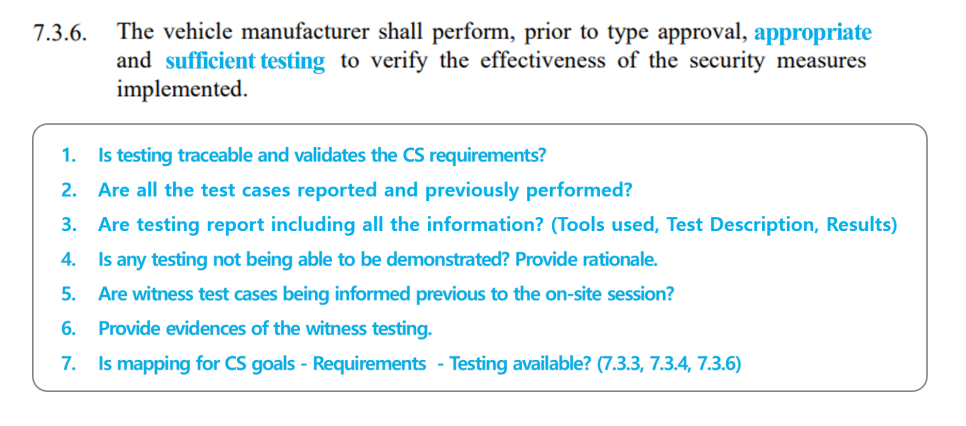

TARA (Threat Analysis and Risk Assessment) and security testing are closely related to each other. The TARA procedure in ISO/SAE 21434 is depicted in the above illustration. Notably, the processes in the blue box evaluate asset attack scenarios, attack path, and attack feasibility. Through these processes, the CAL (Cybersecurity Assurance Level) is decided by determining risk value with the target's threat.

The expertise and experience in cybersecurity testing play pivotal roles in these processes. The steps of identifying threats, formulating scenarios, charting attack paths, and assessing feasibilities are grounded in hands-on experience rather than abstract concepts. In other words, only when various experiences are integrated into TARA, the comprehensive evaluation of potential cybersecurity threats to controllers and vehicles can be conducted.

Furthermore, TARA is a significant benchmark in cybersecurity testing. TARA defines various assets within the controller and identifies potential security threats. Once threats are identified from TARA, security goals are derived, followed by attempts at implementing mitigation measures. The subsequent security tests ensure the system is safeguarded from these cybersecurity threats. By leveraging various test cases crafted based on the Red Team's experience, a variety of attacks are simulated to identify any other potential threats or vulnerabilities, ensuring comprehensive protection against cybersecurity threats.

Essentially, since security testing benchmarks originate from TARA, performing both TARA and security tests within the same company results in enhanced synergy. FESCARO maintains distinct teams for TARA and security testing to ensure an objective approach.

4. Trends on Attack surface

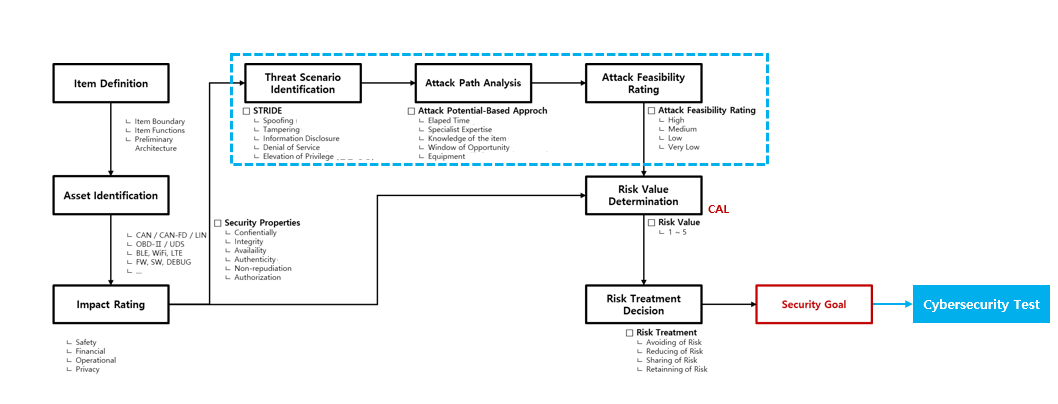

Modern vehicles are equipped with diverse communication capabilities, which means they present multiple potential attack surfaces. Let me explain this with some examples.

Take, for instance, the RF/LF communication employed by a vehicle's smart key. It utilizes a rolling code as a protective measure against replay attacks. Through the vulnerability of a weakly designed/developed rolling code, attackers can sniff and replicate the victim's normal door lock/unlock signals and unlock the vehicle by bypassing the rolling code security features.

If this rolling code is poorly designed or implemented, it can become a vulnerability. An attacker might be able to sniff and replicate the regular signals used to lock or unlock the vehicle, effectively sidestepping the rolling code's security protocols.

Furthermore, if an attacker manages to enter the vehicle, it's possible to target the navigation system via the USB port. In such a scenario, malware could be introduced to extract sensitive personal data, such as contacts, call logs, and recent destinations, from the system.

These attacks are entered through external access points. Yet, our studies have highlighted instances where intrusions were orchestrated from within the vehicle itself. In a particular case, an attacker accessed the vehicle's internal network by removing its bumper and connecting to the headlamp controller. By introducing a malicious message into this controller, the body control module was deceived into thinking the smart key was inside the vehicle. Consequently, the attacker was able to unlock the vehicle, start it, and drive, all without the actual smart key. This breach was feasible because both the headlamp and body control controllers operated on the same CAN bus.

Lastly, Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS), which can be viewed as the early stage of autonomous driving, have controllers such as LIDAR/RADAR/CAMERA that also represent significant attack surfaces. If compromised, these can cause abnormal behavior during driving, endangering passengers. This aspect is of particular research interest to FESCARO.

5. Automotive password-hacking scenarios/techniques

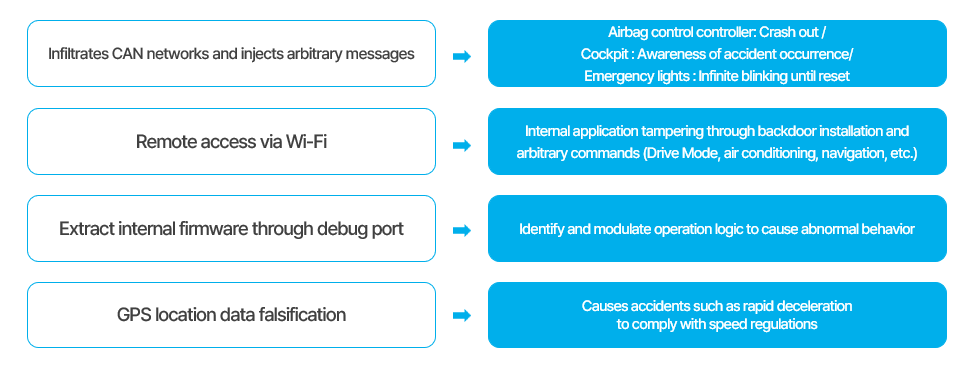

The following is an explanation based on what the FESCARO's Red Team actually has done. Initially, the team accessed the CAN network within an actual vehicle and sent random messages to the remote key controller using our own CAN tool. Their actions led to a Crash out in the airbag controller, triggered by a particular message. This resulted in an issue where the cockpit indicated it as an accident and caused the emergency lights to blink without stopping.

Subsequently, the team successfully infiltrated the vehicle's system via WiFi. They managed to restart the navigation system and tampered with both the video and audio through a backdoor in the navigation system. This attack revealed a vulnerability that could allow an attacker to alter every navigation function, including the Drive mode and air conditioning settings.

Regarding a standard controller that lacks security at the debug port, there's a possibility of extracting its internal firmware through this port. Should someone dissect this firmware and pinpoint, modify, and then update its operational logic, it could lead to the controller malfunctioning or becoming inoperable.

Furthermore, the GPS data of a vehicle in motion can be manipulated to falsely show it's in a different location. This is a grave concern; for instance, if the GPS data of an autonomously driving vehicle is changed to suggest it's in a child safety zone, the vehicle might suddenly slow down to the set limit, risking an accident.

By examining all attack surfaces on the vehicle, the team designs attack scenarios. Based on these scenarios, we then develop test items and formulate test cases.

6. How is the security test carried out?

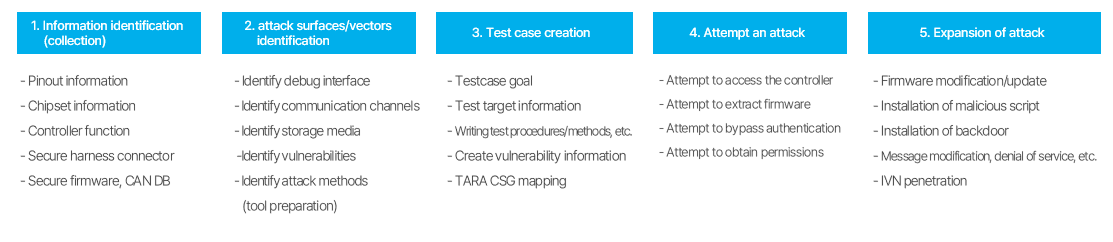

The security testing process encompasses five primary stages. The first stage involves gathering relevant data, which consists of details related to MCU and AP chipsets, pinout information, functionalities tied to controller input/output, and specifics of CAN messages. These details can be sourced from functional manuals, design specifications, chipset data sheets, and discussions with staffs in charge.

The subsequent stage involves identifying both attack surfaces and vectors. Attack surfaces refer to the attack points of the target controller, while attack vectors describe the techniques or methods employed for the attack. For controllers that use MCUs, attack surfaces encompass debug interfaces like JTAG, UART, and USB. Communication channels such as CAN, Ethernet, Wi-Fi, NFC, Bluetooth, and RF also serve as attack surfaces. Additionally, data storage units, including flash memory or storages can also be attack surfaces. Attack vectors include sniffing to analyze communication data, MITM to intercept messages or signals after sniffing, spoofing to falsify intercepted information, and desoldering to extract firmware. Once the firmware is accessed, a common attack vector is the reverse engineering of the binary code to uncover vulnerabilities.

The third stage involves crafting a test case. This primarily encompasses details about the controller, the objective of the test, the strategies and procedures for the attack, and information about potential vulnerabilities. Furthermore, we evaluate the attainment of the cybersecurity objectives by referencing the criteria set out in TARA (Threat Analysis and Risk Assessment) and mapping them to the test case.

The fourth and fifth stages are where the actual attack is performed. The objective is to gain control over the controller. After gaining this control, the aim is to breach the vehicle's internal network by altering its firmware, embedding malicious scripts and backdoors, and initiating denial-of-service attacks to broaden the scope of the attack.

7. What should be conducted during security testing?

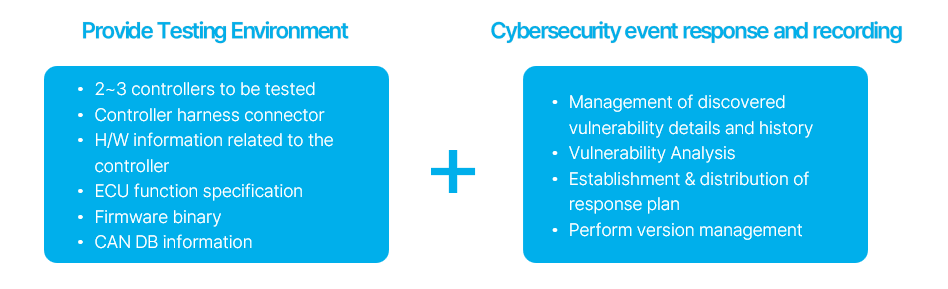

Two primary tasks are essential. Firstly, we need to ensure a conducive environment for seamless testing. Two to three controllers to be tested, including spares, are required, and in this case, controllers with cybersecurity solutions applied are helpful for verification. Furthermore, providing specifications and manuals for the controller that can aid in discerning the harness connector information and controller relevant hardware information. Additionally, sharing the controller firmware binary and CAN DB information will help with quick and smooth testing.

The following is a section on event response and recording of vulnerabilities discovered as a result of testing. This approach aligns with Section 8 (Continual cybersecurity activities) of ISO/SAE 21434. It's advisable to keep track of the details and history of identified vulnerabilities, conduct vulnerability analyses, create and disseminate response strategies, and oversee version management.

8. Difference between

controller-based testing and actual vehicle testing

Even if the same test case is used, testing individual controllers alone and testing them in an actual vehicle may produce different results. Often, a controller is designed to activate its features or function properly only when connected to a CAN network, receiving profile signals from other related controllers. In this case, when testing individual controllers alone, the proper checking of input/output signals and messages is unattainable, making testing within a real vehicle environment more effective.

![]()

![]()

■ Webinar Reviews

* Hoon Noh "It was a valuable time as there had been no webinars on VTA cases before. It was interesting since the details were difficult to experience unless OEM."

* Taek Jeon "The practitioners, especially the mock hacker, explained the cases in detail and were very helpful, and it was beneficial to learn how TARA and mock hacking are combined."

* Gyu Kim “Through this webinar, I became motivated to understand and learn about cybersecurity in depth.”

* Ki Song “It was great because it was an opportunity to ask practical questions that were not easily asked anywhere else in various industries and receive answers from experts.”

* Gook Jeong "I think it would be better if the questions in advance were covered in more detail, and if the explanation of the technical aspects and the mock hacking process were also more detailed."

* Gyo Jeong "I was very interested in the topic because it was highly related to the work I was doing (CSMS), and it was a helpful webinar. I would like to participate in following webinars as well."

* Jun Lee "The format of the experts' answers to the preliminary questions was efficient, and I think this type of format can become a culture unique to FESCARO."

* Soo Lee “In the future, I think it would be a good idea to hold paid seminars or training on more in-depth topics that are difficult to cover through webinars.”